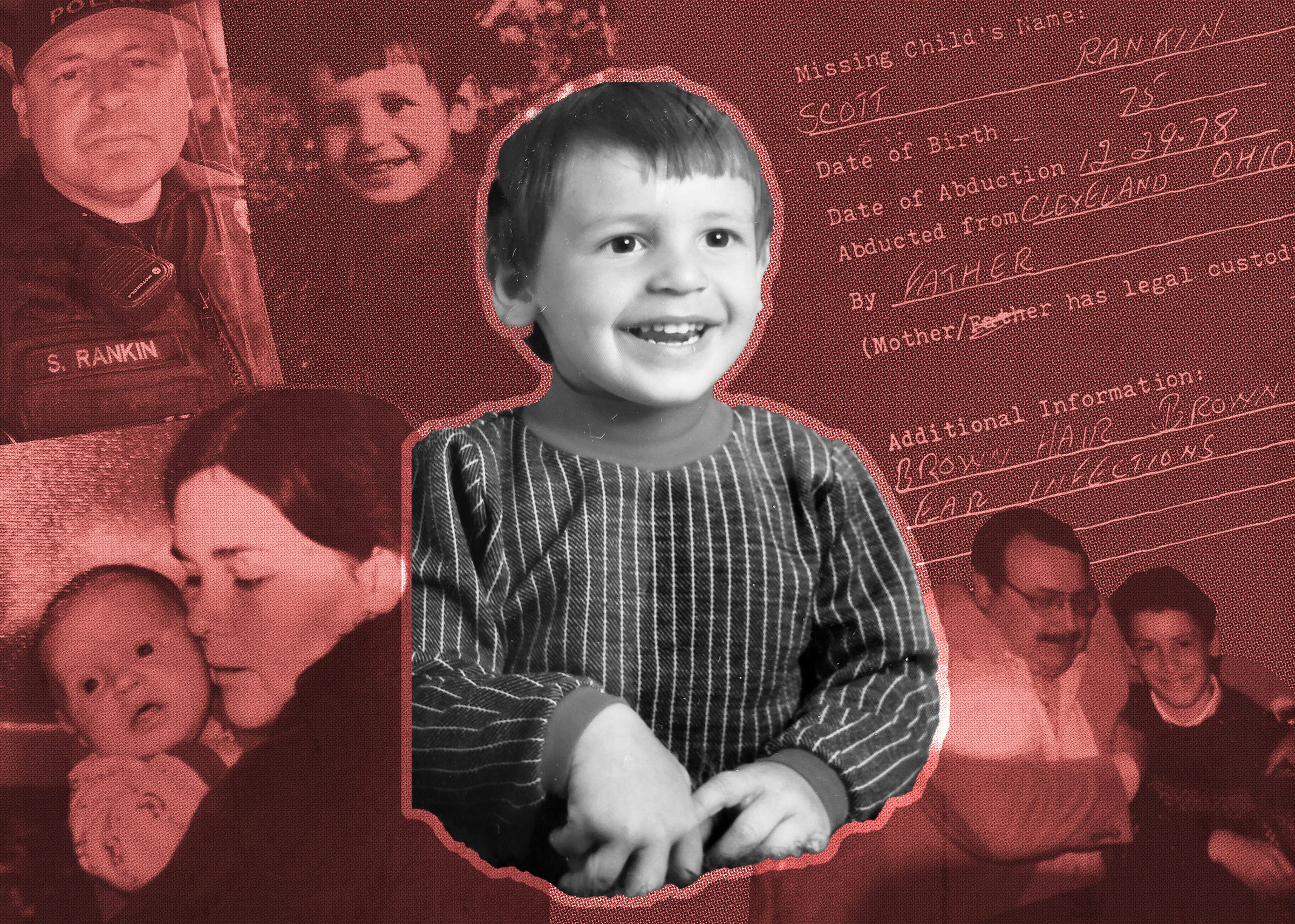

A Missing Child of the 1980s, All Grown Up

Scott Rankin’s father hatched an elaborate plot to kidnap him and start a secret life, while his mother searched desperately for six years. That was only the start of Scott’s traumatic life journey.

One morning in 1984, the school principal walked into the classroom where I taught fourth grade and whispered to me, “Scott is a missing child!”

I looked at 9-year-old Scott, who was present in my class that day. I was quite aware what was implied. The term “missing child” had been seared into the nation’s psyche in the 1980s following a few high-profile cases, including the kidnapping and murder of 6-year-old Etan Patz in 1979. None of us at the school had any idea that Scott had been kidnapped from his own home just a few months before Patz.

The principal explained that Scott had been kidnapped by his father, and over the past six years, including the four-plus he’d been enrolled in our school, his mother, who lived on the other side of the country, had been desperately searching for him. I did not know the depth of the story beginning to unfold. It would be weeks before I understood the immediate implications for Scott and his family — and decades before I learned of the full dimensions of Scott’s remarkable experience.

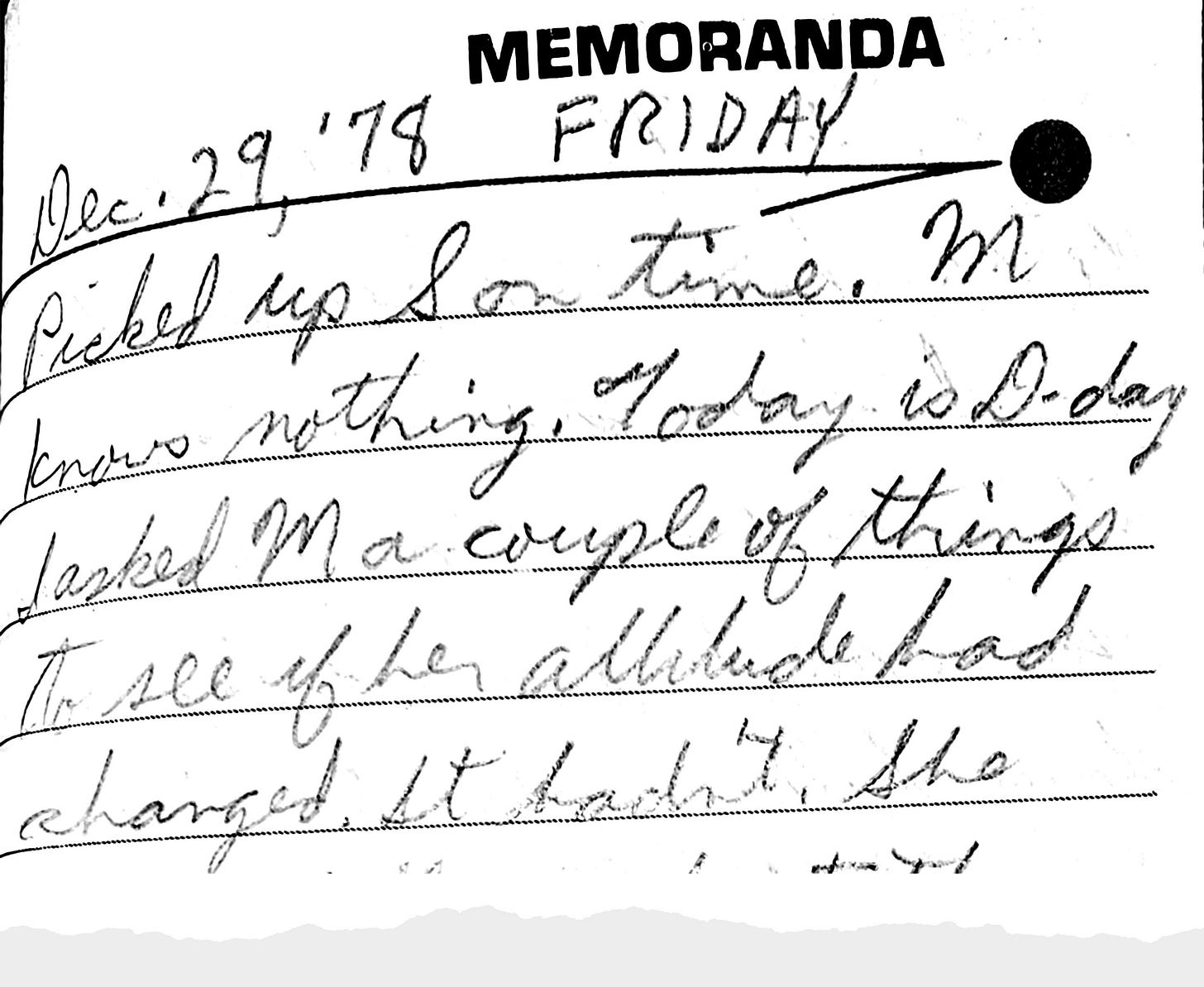

12/29/78, I picked up Scott on time. Martha knows nothing. Today is the day…I have reached the point of no return.

— Entry in Scott’s father’s journal

My first encounter with Scott had occurred the previous year, when he was 8 years old, and it had resulted in a memorable tantrum. That day, I was supervising several classes together for gym. The school rules forbade black-soled shoes because they scuffed up the gym floor. Students with street shoes removed them and took part in their socks. Scott refused to take off his shoes and made a scene about it. I let the disobedience ride and focused on supervising the other 75 students. Other staff members had dealt with Scott’s outbursts before. The principal had become aware of Scott’s temper on his first day of kindergarten, when he threw a large chair across her office.

The following year, I became more familiar with Scott as his fourth-grade homeroom teacher. I soon realized that telling him to remove his shoes was not the only issue that could lead to a meltdown. His temper was unpredictable. He might become upset during a transition from one activity to another, or in the middle of a lesson, or when working on a task.

I tried to address Scott’s conduct by allowing him space and time to calm down. I arranged his desk to be close to mine so I could be more responsive and proactive. I did not raise my voice and I did not confront him. I hoped that my patience, consistency and occasional humor would win Scott over. I also noticed that he enjoyed staying after school to help in the classroom, and I framed the activity as a reward rather than a punishment.

I knew Scott was volatile, but I had no idea about the traumatic experiences that were the source of his behavioral and emotional challenges. I only started to learn about them that day that the principal walked in.