Daughters of the Bomb: A Story of Hiroshima, Racism and Human Rights

On the 75th anniversary of the A-bomb, a Japanese-American writer speaks to one of the last living survivors—and traces connections from Malcolm X to the fight to end nuclear war.

In honor of Nihon Hidankyo, a Japanese organization of atomic bomb survivors, being awarded the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to abolish nuclear weapons, we’re republishing this important Narratively Classic here this weekend.

I keep a red file folder, its edges faded from nearly three decades of exposure to dust and light. Inside, the title words I typed in 1991: “The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima.” It is the first research paper I ever wrote. Tucked inside of the folder’s front flap are three stapled index cards, each one with reference titles written in smudged pencil. The first book listed is the one that mattered to me most: journalist John Hersey’s 1946 nonfiction classic Hiroshima. The book’s scenes, vivid and wrenching, are lodged inside my memory. Particularly this one, about the Rev. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, pulling bomb victims from a sand pit: “He reached down and took a woman by the hands, but her skin slipped off in huge, glove-like pieces.”

Hersey introduced me to Mr. Tanimoto, a man who wore his hair parted down the middle and moved through crowds of mangled, dying people, bringing water and apologizing: “Excuse me for having no burden like yours.” At a time when Japanese people were roundly excoriated in the U.S., portrayed as demons, yellow monkeys, and savages deserving of death, one historian claimed Hersey’s book transformed “subhuman Japs back into Japanese human beings.” His omniscient, controlled voice felt godlike and all-knowing, free from authorial editorializing. He was hailed as a writer who “let ‘Hiroshima’ speak for itself.”

When I first read the book in 1991, I was struggling to make sense of my place among some Americans who still — 46 years after the bomb — saw someone like me as subhuman. I was a child with a Japanese immigrant father (he was born three years after the bomb) and a white mother. I grew up in a small Midwestern town as one of only a handful of Asians. There was name-calling: “Chink.” “Gook.” “Jap.” There were days when white kids threw rocks at me on the playground or recited the all-too-common phrase: “Go back to where you came from.” Being anti-Asian was an easy fallback for your garden-variety middle school bullies. I have memories of hiding in a blue paint-chipped bathroom stall, wondering what was wrong with me.

White mothers do their own kids of color no favors by claiming colorblindness. But my father did not mention such racial matters either. There is a phrase in Japan, “ba no kuuki wo yomu,” which means “to read the air.” It is an unspoken practice of sensing a person’s feelings, or a situation, without words. Decades later, when I had my own kids, my mother would tell me that she and my father watched a documentary together, early in their marriage, about the internment of Japanese-Americans. It ended, and they sat there in silence. Neither knew how to talk to the other about racism, much less their own kids. Uncomfortable facts fluttered in the atmosphere, never to be addressed.

When my teacher, Mrs. Ott, assigned a book report about a historical event in middle school, I asked my father what I should write about.

“What about the atomic bomb they dropped on Japan?” he said, as if we had discussed this event my entire life. I had no idea what he was talking about. I only knew that once I had stumbled across my father cleaning the hot tub he had built with slabs of wood in our backyard. Staring at the sky as it began to drizzle, he muttered something about how Americans never knew “black rain.”

“Two hours after the bomb dropped a strange black rain began to fall,” I would write a few years later in my research report. “Big as the ends of one finger. This strange rain left greasy black stains that wouldn’t wash off. It was called acid rain. … It could altar [sic] the structure of cells inside the human body.”

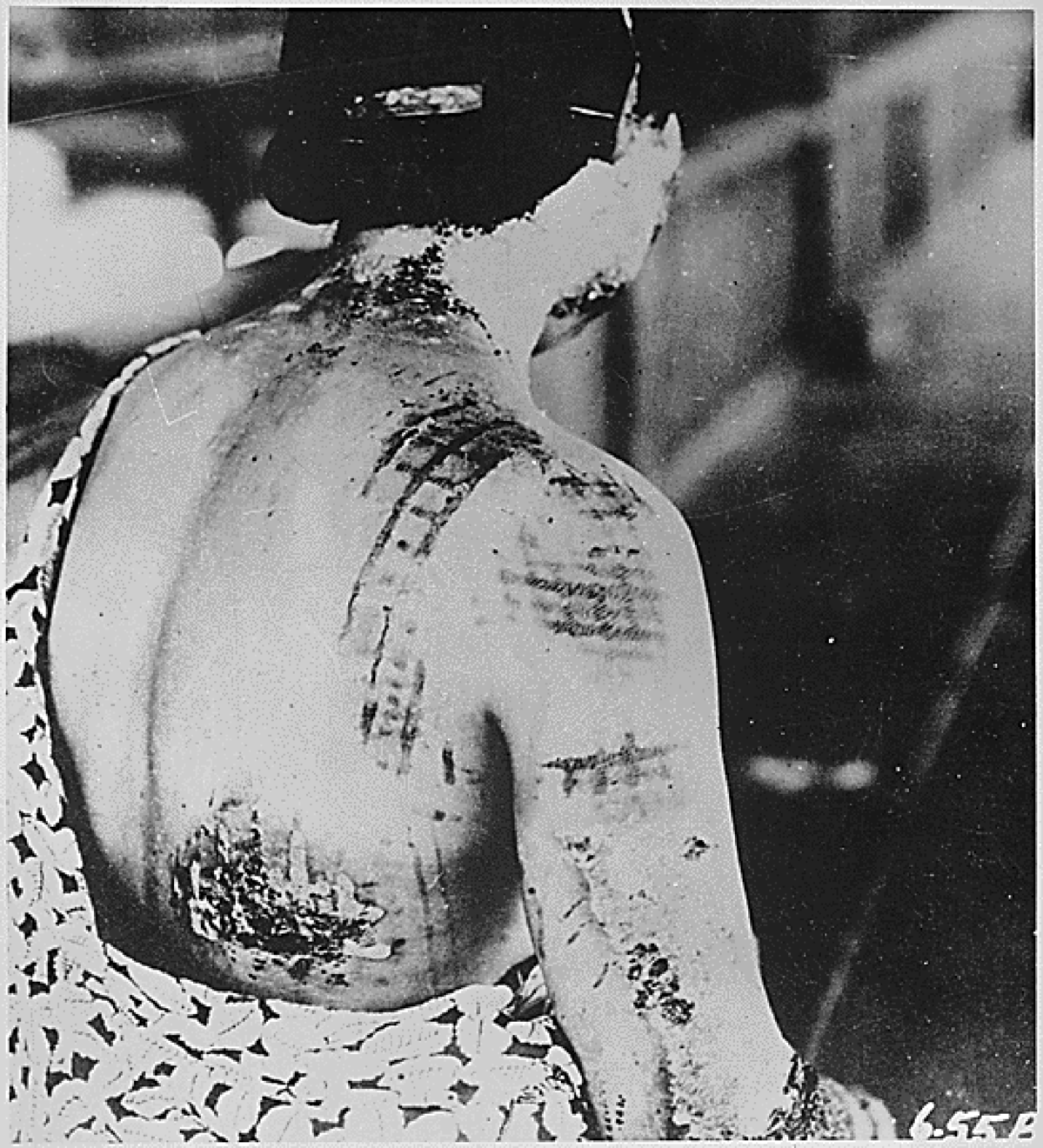

Reading Hiroshima, I learned how Mr. Tanimoto ran to look for his wife and baby, encountering hundreds of fleeing people along the way. “Many were naked or in shreds of clothing,” Hersey wrote. “On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns — of undershirt straps and suspenders.” The shapes of flowers from kimonos seared onto their skin.

My personal torment suddenly fit into a context of racism and war. Classes at school did not teach me about the internment of Japanese-Americans, nor about all of the rest of the groups deemed subhuman. So, as a teenager, I went searching for more books that did.

I was 15 when my grandmother in Osaka died. I flew to Japan with my father and brother. We lit incense and prayed at an altar inside of my grandmother’s home, which smelled grassy from the tatami mats. Her house slippers lay on the kitchen floor, her purse hung on a door, her bedroom closets stacked with satiny kimonos wrapped in tato-shi paper.

Late at night my family shared stories of my grandmother. My uncle told me how she ran from World War II bombs, holding him as a baby in her arms. A few days later, we boarded a bullet train bound for Hiroshima.

Mr. Tanimoto did end up finding his family on the day of the bomb. His wife had been at home when everything around them exploded. She told her husband how “the wreckage had pressed down on her, how the baby had cried,” as Hersey wrote. “She saw a chink of light, and by reaching up with a hand, she worked the hole bigger, bit by bit.” She climbed out with their daughter, Koko, wearing a blush-colored baby gown.

Koko Kondo’s story began where Hersey’s book left off. Kondo, I would later learn, grew up with an unfiltered view of the bomb’s devastation. Orphan girls showed up at her church when she was a child, their lips burned into their chins, eyelids seared off, fingers melted together. Her father founded the Hiroshima Maidens project, to raise money for reconstructive surgery and health care for Japanese women and girls scarred and mutilated by the atomic bomb. Kondo hated the people who did this to them.

When Kondo was 10, she boarded a plane to America. Her father was already en route to the U.S. to speak on behalf of the Hiroshima Maidens. Her mother had been summoned, along with Kondo and her three younger siblings. They did not have passports and did not know why it was so important for them to come to the U.S. right away. But when they arrived at the airport, one of its employees greeted them and said: “We have been waiting for you.” Within minutes, her family members received their passports.

They landed in Los Angeles, and after settling in, Kondo’s family was whisked to the NBC studios, where her father was already waiting backstage to appear on the television show This Is Your Life. What happened next would go down as one of reality television’s most exploitive moments. I cannot watch the clip without feeling queasy and disgusted.

Mr. Tanimoto thought he was there primarily to talk about the Hiroshima Maidens. He did not know that he would end up walking through the day of the bombing before a live audience, fake sirens blaring on stage, a melodramatic host narrating with tawdry music and theatrics, in between commercials for nail polish. Tanimoto, in the black-and-white video, looked confused, emotional, and even frightened as people from his life walked on stage one by one. Then, a shadowy figure behind a screen spoke into a microphone: “Looking down from thousands of feet over Hiroshima, all I could think of was, ‘My God what have we done?’”

Kondo and her family had no clue before they arrived, but the producers had invited Robert A. Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. “You’ve never met, you’ve never seen him,” the host said, “but he’s here tonight to clasp your hand in friendship.” Lewis emerged, taller and stockier than Tanimoto, who seemed solemn and tense as he shook his hand. Lewis said it again: My God what have we done?

The other pilot flying the Enola Gay, Paul Tibbets, died without ever expressing regrets. But when Kondo heard Lewis reveal his conscience on TV that day, she realized: “He’s a human being like me.” Today, Kondo tells audiences that in that moment, she decided to hate war instead of him. “I walked slow, just like a crab, toward him,” Kondo would later recall. She reached for his hand, and he held hers back. Kondo would speak of feeling grateful to Lewis, for helping her realize this shared humanity.

But when I watch that television moment from 1955, seeing Kondo as that empathic little girl, thrust into such a grand orchestration, I can’t muster that same mercy and reconciliation. I can’t help but think of how people of color, throughout history, have been expected to forgive their oppressors and murderers so white audiences can feel better.

I also know that every story is more complicated than our meaning-seeking brains sometimes allow them to be. I know a human being can be a living contradiction of evil and good. A heart can feel compassion for the same person for whom it also holds contempt. And I know that a single soul can hold within it two opposing sides of the same war. No matter the nuances, I know too that at some point one side always wins.

In the days after my grandma in Osaka died, I carried a spiral notebook through Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and its museum, taking notes on the video testimonies from survivors: “I remember seeing a picture of hell once,” a survivor said, “but it had green in it. Hiroshima had only three colors, red, black and brown … and in the middle people were screaming.”

I stood before cascades of multicolored paper cranes. I photographed the charred tricycle of 3-year-old Shin-ichi, who had been riding in front of his house when his father saw the flash of light. “He died that evening,” I wrote. “The father buried the young boy in his backyard alongside his tricycle, so it would continue to be his playmate.” Shin-ichi’s father later removed his son’s remains for a proper burial and donated his tricycle to the museum.

If there is genetic predisposition to becoming a writer, mine most likely came from my mother’s side. Her father, my grandfather, fought in the U.S. Army in Germany during World War II. He also taught memoir writing classes to retirees at his local community center until he was 88. Four of his five adult children wrote their own books.

My American grandfather was a gentle, jovial man who tutored me in math and encouraged my journalism. In his own life chronicles, he wrote of his platoon assignment in Lucherburg, Germany: “The now crusted route along a lonely dirt road led past a pair of dead horses, which smelled bad enough for us to walk around. Then, past a face-up fourteen-year-old lad in enemy uniform. Tough for them, unimportant to us.” My grandfather never actually wanted to be there, fighting in a war. His own mother had emigrated to the U.S. from Germany.

It was through my grandfather’s stories that I also learned more about my grandmother’s brother, Jim (my great-uncle), a graduate student of the University of Wisconsin who studied nuclear physics. Jim had been recruited right out of college to work on a top-secret project in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Years later, the family would come to find out what Jim had been working on all of that time: the Manhattan Project. My American great-uncle, as it turned out, helped build the very same atom bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, and three days later, Nagasaki.

It was a stunning piece of family information that didn’t really sink into my psyche for years.

Was the family proud of his work? I eventually asked my aunt.

“Yes. Americans were told that this was what ended the war,” she replied. Scientists “were there to split atoms. Each person had their job to do — a small part of the big picture. Very few people knew what the end result was supposed to be.”

And with those words, my mind flashed again to that end result: Mr. Tanimoto lifting slimy living bodies and carrying them away from the tide, as Hersey described. Tanimoto repeating to himself: “These are human beings.”

With Hiroshima, and with the story of my great-uncle Jim, I grappled with my own contradictions. We are often taught to embrace nuance, in literature and in life. In Latin, the word nuance began with “nubes,” or clouds, floating in the air. In French, nuance became shades of color, the mixing of colors, variations in tone. Check more than one box, I learned growing up. Include every part of yourself. Be ambiguous.

For me being biracial meant figuring out on my own that this society, actively racist against me, also wanted to fold me into a kind of racelessness. When it really came down to it, I realized such a middling existence was a lie. I love all of my family. But I have only ever walked through this world as an Asian-American. If internment came, my whiteness would not have spared me then, just as it would not now.

The atomic bomb spared Koko Kondo’s father’s life. But somehow it seemed to steal him away from her too. Her father never abandoned his mission to help survivors. It so completely consumed him that for much of Kondo’s life, she felt as if he had forgotten her.

Kondo explained this reality to me, these contradictions she harbored growing up, nearly three decades after I first read about her as the Rev. Kiyoshi Tanimoto’s baby in Hersey’s book. I felt humbled in her presence, even though we were 5,500 miles apart, meeting over Zoom in the midst of our shared Covid-19 reality.

Kondo, now 75, is a spirited woman with a crown of silvery hair, wispy eyebrows, and a beauty mark on her left cheek. She sat in the back of her church, in the city of Miki, Japan, raindrops tapping on the rooftop, her back facing the empty pews and pulpit.

When she was a child, her father, the reverend, was always traveling, speaking, working on the Hiroshima Maidens project. “I wanted to go out for a walk with him, or sit on his lap, but there was no way I could do that,” Kondo told me. “I missed him so much.”

As Kondo grew older, she learned that the radiation inside of her body had ravaged any chance of her bearing children. A man she had hoped to marry left her because of it. Kondo became an atheist. She went to college in the United States. With every anniversary, her father continued to speak about the bomb, living his commitment to help those that it hurt. Meanwhile, Kondo told herself that her father’s service-driven path would not be hers.

Kondo did not have to be a frontline activist for people to know that she hated the atomic bomb. They could sense that much without articulation. The survivors of the atomic bomb — known as “hibakusha” — often found themselves shunned in Japanese society, viewed as contagious or abnormal. Some hid their hibakusha status from their own family members, or pledged never to speak of the bomb, for fear of discrimination or alienation. Noble as her father’s activism was, Kondo told herself for a long time that his mission would not be hers to follow.

But there is no playbook for what happens to the little girl who realizes that little girls like her can be hated, maimed or murdered for who they are and where they are from. Parents cannot predict whether their child will grow up broken by such harsh truths. Or whether she will figure out a way to one day feel empowered to speak out.

When her father was the same age that Kondo is today, he tripped and tumbled to the ground. Mr. Tanimoto broke his chin and jaw. Suddenly, the man who had spent his whole life speaking up for Hiroshima survivors had lost his ability to talk at all. He never regained his words.

He died soon after. By then, Kondo’s outlook on his life’s mission had changed. She was one of the hibakusha, whose ranks grew thinner each year.

You can live a kind of middling existence for a long time. Not firmly outspoken on a side. “Reading the air” is a kind of social and emotional intelligence, a way of silently tuning into other’s feelings. But it can also be about following a majority, reading the room to fit oneself ambiguously into a scene without disruption.

Kondo had lived in the U.S. during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, first at a junior college in New Jersey, and then as a student at American University in Washington, D.C. She learned about freedom protests for Black Americans, and she came to admire the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who wrote: “The tendency of most is to adopt a view that is so ambiguous that it will include everything and so popular that it will include everybody.”

Kondo realized her own calling when it came to social justice was to take on the legacy of Hiroshima. She decided she did not just want to see nuclear weapons controlled or curtailed. She wanted them abolished. And she knew that for as long as she still had her voice, she would continue to tell their story — Hiroshima’s story — to anyone who would listen. Today, Kondo has one unequivocal pursuit: a nuclear weapon–free world. “For the sake of the children,” she told me.

The second time I visited Hiroshima, in 2017, I brought my daughter. She was just 4, standing before the skeletal remains of the Atomic Bomb Dome, a structure that had been directly underneath the explosion yet somehow avoided total destruction. My daughter, in a peachy pink button-down dress and purple sneakers, curled her fists and furrowed her brows. We tried to explain the atomic bomb that day. The senseless loss of lives. I would not show her the charred tricycle, which is still inside of the museum.

My mixed-race daughter, who has my Japanese and white ancestry, is Black. Her father, my husband, was born in Jamaica, raised in Flatbush, Brooklyn, where he was slammed on the hoods of police cars by cops when he was a kid playing tag with his friends in the streets. He was harassed so often for “fitting the description of a suspect” that his mom, fed up with the last time she sent him out for milk and police stopped him, filled out a scholarship application for a boarding school in Connecticut. When he was accepted, she sent him away at 14. “I didn’t want anyone to take him away from me at that age,” she told me. “Man, those policemen were a pain in my neck, you hear me?”

Neutrality is not a stance on racism, in between racists and anti-racists. There is one side, and then there is the other. Today, our daughter, now 7, has memorized George Floyd’s name. She knows he was killed by police. She has asked us: “Would police ever hurt a little Black girl?” To which my husband replied: “They might.”

My daughter is an empathic child, three years younger than Kondo was when she met the co-pilot of the Enola Gay. She has marched with Black Lives Matter protesters and stared at the remains of the atomic bomb. There is no playbook for what happens to the little girl who realizes that little girls like her can be hated, maimed or murdered for who they are and where they are from. You can shield her from charred tricycles and viral police brutality videos, but one day she will know.

As a teenager, understanding Hiroshima and the history of racism against Japanese people while simultaneously experiencing prejudice myself awakened my own interest in civil rights, putting me on the path to follow in Hersey’s footsteps and become a journalist.

In Hiroshima, Hersey chose his subjects carefully: the widow raising kids, two doctors, a German Jesuit priest, the young woman working to support her parents, and the Rev. Kiyoshi Tanimoto. If you read between the lines of the book, Hersey’s subjective choices of who to include, and how to unfurl carefully culled details through his subjects’ eyes, did not just give the book its emotional power. Taken together, these choices laid out a clear point of view against the atomic bomb. Hersey’s son told The New Yorker that the journalist had “a strong sense of right and wrong,” which colored his approach to reporting and writing the story.

Hiroshima sparked my interest in reading other books not assigned in classes. By high school, I started with Ronald Takaki’s Strangers From a Different Shore. Monica Sone’s Nisei Daughter. I moved on to read Booker T. Washington. W.E.B. DuBois. Malcolm X. I did not know until many years later how some of the same Black voices I grew up reading and thinking about were among the earliest voices to speak out so urgently against the atomic bomb.

Martin Luther King called for the abolition of nuclear weapons, linking the idea to racial harmony: “We must transform the dynamics of the world power struggle from the negative nuclear arms race, which no one can win, to a positive contest to harness man’s creative genius for the purpose of making peace.”

Setsuko Thurlow was 13 when the bomb hit. “I found myself crushed, pinned under the collapsed buildings,” Thurlow, now 88, recently recalled. “Then I started to hear the whispers of the girls around me. ‘Mother helped me. I am here. God help me.’ So I knew I was not alone in that total darkness. I was surrounded by my classmates.” Thurlow described how she managed to escape the rubble. But about 30 girls who had been in the room with her ended up burning alive. Over the years she came to realize that the atomic bomb was not dropped out of military necessity. Historians, Thurlow said, had uncovered a “racist reason.”

One of these historians, Vincent Intondi, in his painstakingly researched 2015 book, African Americans Against the Bomb, laid out how Black leaders placed nuclear disarmament into broader discussions of civil rights, colonialism, militarism, racism, peace and human rights. Writers such as Langston Hughes, as Intondi pointed out, saw the decision to bomb Japan as racially motivated. Hughes asked: “Why did the United States not drop atomic bombs on Italy or Germany?” Meanwhile, DuBois advocated for outlawing atomic energy used for bombs, and connected Japan’s nonwhite victims to the freedom struggle. “If power can be held through atomic bombs,” DuBois wrote, “colonial peoples may never be free.”

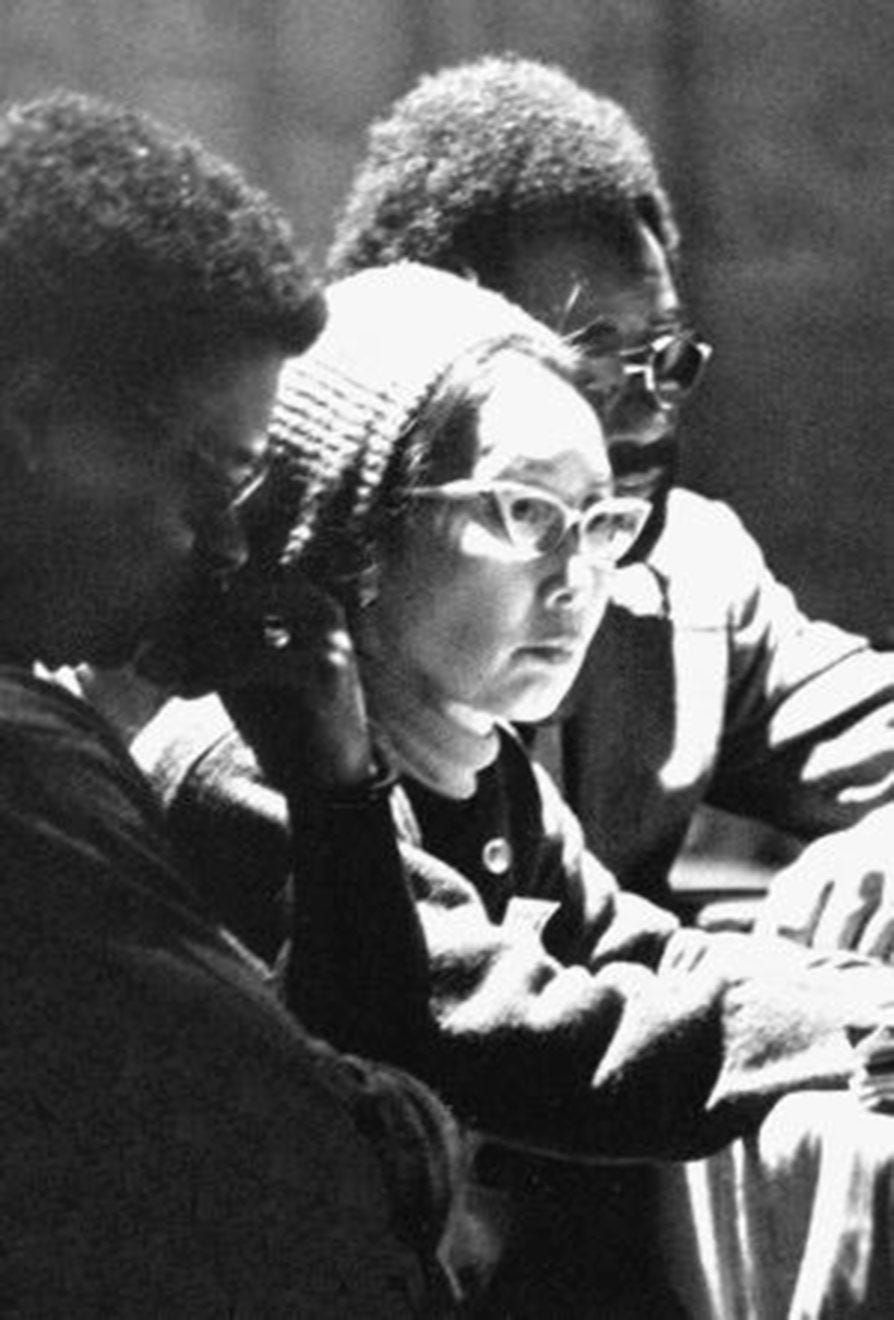

In 1964, the Japanese-American activist Yuri Kochiyama invited a group of hibakusha to her Harlem apartment. She also invited Malcolm X, who surprised everyone when he showed up and knocked on the door. “You have been scarred by the atom bomb,” he told the Japanese survivors. “You just saw that we have also been scarred. The bomb that hit us was racism.”

Eight months later, Malcolm X was gunned down in a ballroom in New York. Kochiyama had developed a friendship with him and was in the ballroom when he was shot. As others fled, she rushed toward him, picking up his head and putting it in her lap, begging him to stay alive.

As Ronald Takaki and other historians have documented, President Harry Truman, who gave the thumbs-up to drop the bomb, penned a letter to his future wife, Bess, in 1911, more than three decades before Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “The Lord made a white man of dust, a nigger from mud, then threw up what was left and it came down a Chinaman. He does hate Chinese and Japs. So do I. It is race prejudice I guess. But I am strongly of the opinion that negroes ought to be in Africa, yellow men in Asia, and white men in Europe and America.”

Today, the nuclear weapons system is still sanctioned by structures of white supremacy and power, under claims of safety and self-defense. It continues to protect those in power, while nuclear testing harms people of color around the world, contaminating food and water resources and exposing residents to radiation. In the 1960s, France conducted nuclear tests in the Sahara Desert in Algeria, and in French Polynesia until 1996. There has been little to no compensation for victims of those tests. The U.S. also conducted nuclear tests in the South Pacific, to the detriment of impoverished indigenous populations.

In Washington State, the Spokane Tribe of Indians has long suffered from health and environmental damage due to a uranium mine for nuclear weapons, which closed in 1981, though cleanup did not begin until 2017. Native American tribes in close proximity to the Hanford Site in Washington State, a decommissioned nuclear production complex, were also exposed to radioactive contamination. And a birth study of the Navajo Nation, which spans Utah, New Mexico and Arizona, found that 27 percent of those tested had high levels of uranium in their urine, decades after the nuclear weapons mines were closed.

The hibakusha know that they cannot undo the past, Kondo told me. She focuses on today, and tomorrow. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which Kondo advocates for, would prohibit countries from developing, testing, producing, possessing, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons. It needs 50 countries to ratify it in order to become law. It currently has 10 to go. The ones that have ratified it so far are overwhelmingly African, Asian and Latin American.

As Black Lives Matter supporters call to defund militarized police departments that claim to protect citizens while using bloody and deadly violence against them, Kondo, along with other hibakusha, question why the same countries that claim to never want to see another atomic annihilation like in Hiroshima or Nagasaki continue to upgrade and preserve their nuclear weapons. We can live with this kind of middling existence for a long time. But there comes a point where it feels like a lie.

From her church in Miki, Kondo talked to me about the strangeness of time, how it all seems to come around full circle. She left atheism years ago to rejoin her father’s Christian faith. As I sat across from her virtually, the blush-colored baby gown she wore through the bombing sat folded on a table beside her. She held up her signed copy of the book Hiroshima, its pages faded from years of exposure to dust and light. She turned to a page depicting her father in those first hours after the bomb, looking for his wife, and the baby they had named Koko.

After decades of hiding or staying silent, in recent years more hibakusha have come forward, reclaiming their place in society, becoming proactive and outspoken, a force in the movement to abolish nuclear weapons. They have done so on the heels of hibakusha like the Rev. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, one of the earliest survivors among them who dared to disrupt the atmosphere.

“My father told me we might not change the whole world,” Kondo told me before we signed off. “But if we tell our story, person to person ... someday.”

And as I looked at Mr. Tanimoto’s daughter’s face, in that moment I could picture the reverend. The man in my literary memory, with his hair parted down the middle, lifting naked, dead bodies out of a stationary boat, saying out loud and into the air: “Please forgive me for taking this boat. I must use it for others, who are alive.”

This story is a collaboration with the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. Read more about the hibakusha fighting for an end to nuclear war, and take the pledge to honor the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki here.

Erika Hayasaki is a journalist based in Southern California, the author of The Death Class and a professor in the Literary Journalism Program at the University of California, Irvine. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Wired, Slate and others.

Brendan Spiegel is the co-founder of Narratively and currently leads Narratively Academy, the site’s education wing.

Noah Rosenberg is the founder and CEO of Narratively.

This story was originally published on August 5, 2020.

Part of the problem is that far too many Americans don't know our own history. When I was in school, I learned very little about the discrimination and prejudiced policies and behavior the US inflicted on women and people of color across history. I learned about the internment of Japanese Americans after I got out of school. Similarly, I can still remember my outrage when, as an adult, I realized just how terribly we'd treated the indigenous people. I knew none of it before.

The same is true of the atomic bombs we dropped. I was taught that we dropped them to end the war but no one mentioned what happened to the people who were there. That's a huge disservice to understanding history and a missed opportunity in developing compassion. However, I was fortunate enough to be in a gifted program in which we did learn more. I still recall the passion with which my 6th grade classmates and I berated a college professor over his defense of the dropping of the bombs. He told our teacher he'd never been challenged like that before. Yay for us but how deeply tragic overall.

Thank you for writing this article, Ms. Hayasaki. I learned a lot and appreciate the work of activists determined to abolish nuclear weapons. More people need to hear their stories.

The Nobel Peace Prize and Erika Hayasaki's account of the effects of the atomic bomb send meaningful messages to all of us. I want to include my friend, Kiyoko Neumiller, in this urgent message. As I wrote in The Seattle Times, Kiyoko was near the epicenter, yet survived the bombing of Hiroshima to become a voice for peace.