✏️🛠️ How to Change Your Story When the Research Surprises You

The hardest part of a big writing project is when your reporting unveils something that doesn’t support your original thesis. What do you do then?

For her book, Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir in Archives (named a Best Book of 2023 by NPR), Amelia Possanza listened to hours of oral history tapes, sifted through archives and retraced the steps of her research subjects across New York City. Next week, she’ll share how to take a similarly exhaustive approach to any research-heavy writing project in the Narratively Academy seminar Reporter, Sleuth, Storyteller, Spy: The 90-Minute Guide to Investigating Like a Pro. Today, Amelia shares some advice on what to do when your research surprises you.

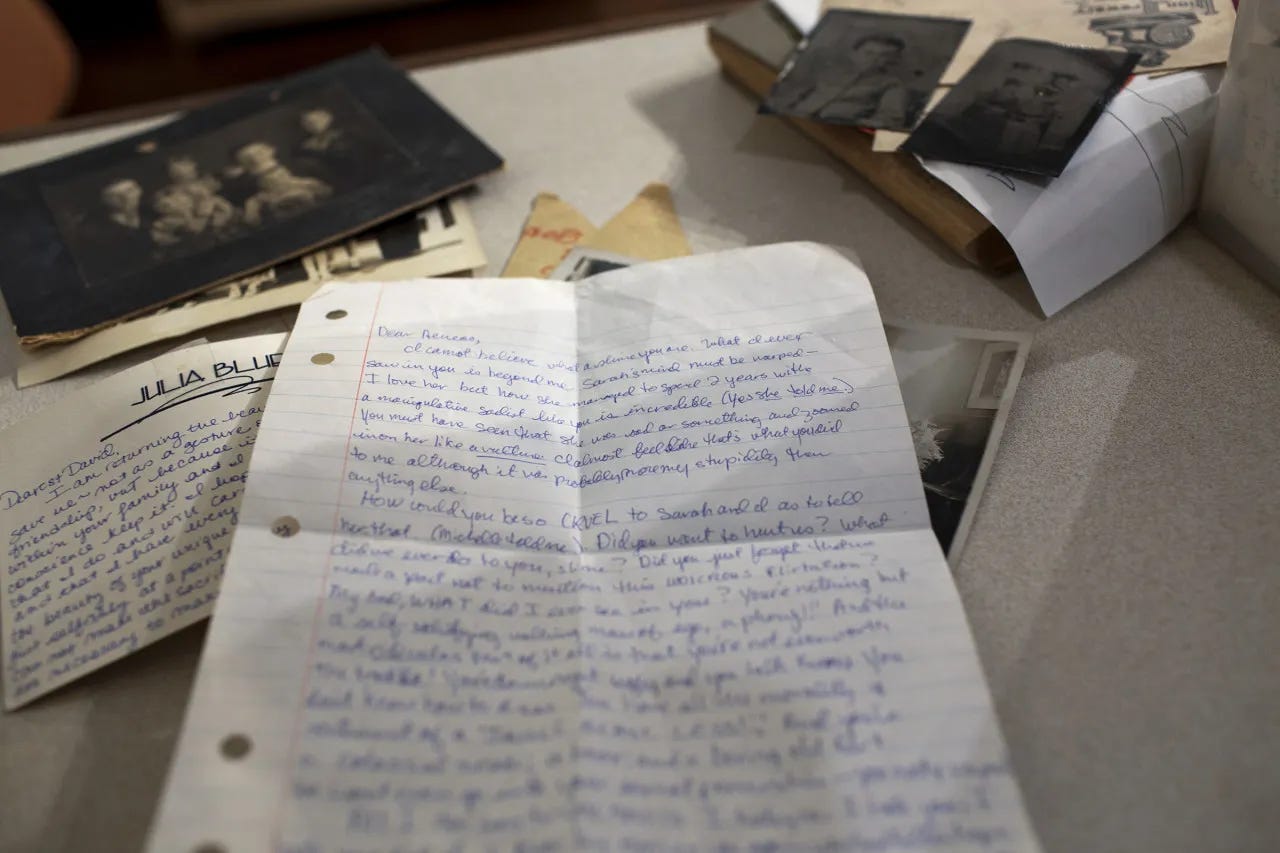

Nothing says the start of a new writing project like a stack of books from the library still held shut by their rubber bands, or a calendar full of new color-coded research appointments and source interviews. When I set out on a new, big research project, I’m filled with nothing but excitement about what I might find. But I’ll also be the first to admit it: Even at this early stage, I already have a sense of what I’m hoping to find, whether it’s just a rough sketch of the argument I’d like to make or a clearer picture of the evidence I’m searching for. Maybe I have a suspicion that the letters I’ve asked the librarian to pull reveal the relationship between their authors to be a romantic one, or a hunch that a particular oral history tape will contain the exact date the lovers met. The pearl hidden inside the clam, if only you know where to look.

The thing is, these hopeful visions of eureka-producing discoveries often dissipate the moment I crack open the first book. My research, whether it’s in a quiet archive or the comfort of my own home, rarely confirms whatever preconceived ideas I arrived with. Maybe the trail I followed was a rumor that had already been debunked years ago. Maybe I had been misled by my own bias.

For example, when researching my own book, Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir In Archives, I was thrilled to read in a commercially published history of the Stonewall Riots that the bar had been named for a little-known, turn-of-the-century lesbian autobiography, The Stone Wall by Mary Casal. So thrilled, in fact, that this became an easy shorthand in my draft’s first chapter for the often-overlooked contributions of lesbians to queer history. When I shared this detail with a fellow writer and historian over coffee, still giddy about the connection, he replied, “Oh, that old rumor? There’s no evidence it’s true.”

Deeper into the research, an even bigger obstacle tripped me up. I had envisioned the book as a series of chapters on romantic couples, largely unknown, that would tell the story of lesbian history in the 20th century. It had been easy to find the first four pairings, but in the later decades, the ’70s and ’80s, I was drawn to stories whose drama lay outside the realm of traditional romance. I wanted to tell these stories, but they didn’t fit into the book I’d planned.

I asked myself, “Where do I go from here? Do I need to ditch the entire project and start again?” As is often the case with revision, each snag I hit was really a sign that something had gone wrong a few steps back. So I went back to my notes to figure out where I had made a wrong turn.

First, I noticed I had taken a few stray notes on historical lesbians that didn’t seem to quite fit the bill as main characters because they lacked the requisite romantic arc, but who still interested me. I wished I had taken more notes on these women because they might be able to tell me if my premise needed to change. Going forward, I vowed, I would take notes not just on the facts I knew would support my initial vision for a project, but also on the seemingly irrelevant details that piqued my interest. Who knew what they might become? Besides, if it’s interesting to me, it will probably keep the reader interested too.

Next, I designated some time to researching these historical queers who I had initially dismissed as extraneous. I was nervous to devote my energy to potential dead ends, particularly with a deadline looming over my head, so I set a timer on my phone before wading into digitized back issues of 1970s lesbian magazines and anthologies put together by feminist presses. When the alarm went off, I didn’t have any concrete information I wanted to fold into the project, but I suddenly realized what kind of material I was drawn to: stories of community care and support. Maybe that kind of love could have a place in the narrative, too. Taking the time to research these stories that originally didn’t seem to fit helped me realize how to shift my overall approach to the book.

That still didn’t solve the issue of Stonewall. I was so embarrassed, my first instinct was to remove any mention of the connection from the story. But if it had been so alluring to me, and to the author of the book I had discovered it in, then the lore must have something bigger to say about what we want out of queer history. I wrote myself into the story, sharing on the page both my excitement at the discovery and my disappointment when I learned it was untrue. Now when I write new nonfiction and am forced to confront my preconceptions in the midst of the research process, I always ask myself: Could I become a foil for the reader, or will my voice become a distraction in a reported story?

It is always hard for me to resist the excitement of diving headfirst into uncharted waters. Now, though, I force myself to take a few moments for some deep breaths to set myself up to approach the material with an open mind. There may be rough seas ahead, but I’ve built a sound boat to weather them.

Ready to get started on your own big research project? Join Amelia Possanza next Wednesday, May 22, for Narratively Academy’s Reporter, Sleuth, Storyteller, Spy: The 90-Minute Guide to Investigating Like a Pro.

Amelia Possanza’s debut book, Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir In Archives, came out in 2023 from Catapult in the U.S. and Square Peg in the U.K. and was named a Best Book of 2023 by NPR, Harper’s Bazaar and Publishers Weekly. Her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, BuzzFeed, Lit Hub, Electric Literature, The Millions and NPR’s Invisibilia.