How I Learned That Treasure Hunting Isn’t Just About the Spot Marked X

After hearing about an armchair treasure hunt that had been running for decades in France, I was intrigued. Little did I know that was just the beginning of the story.

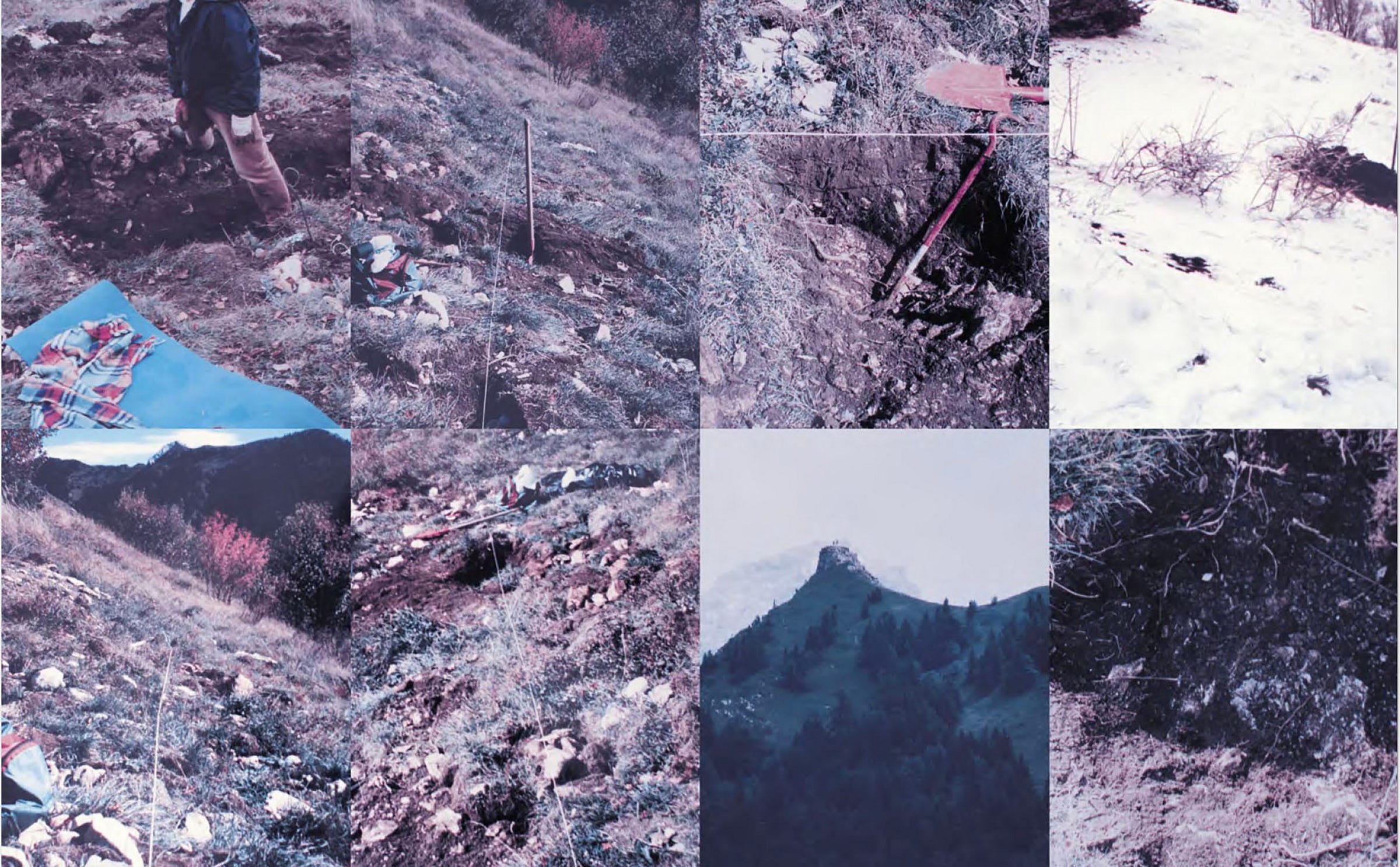

Everybody loves a treasure hunt. Especially one that’s not been solved yet. They’re one of those archetypal things — whether fuelled by hunter-gatherer instincts or just plain old magpie shiny-thing compulsion — that we seem hardwired to respond to. I was no different when I first heard about On the Trail of the Golden Owl in 2022. It’s an armchair treasure hunt that had been running for nearly 30 years in France, in which thousands of owl hunters, or chouetteurs, were still busy poring over 11 puzzles and digging up holes all over the country in search of the titular statuette. That’s a pretty compelling pitch on its own, right?

The hunt is quite well known in France, where I live, because of its longevity. But I first became acquainted with it because the U.K. newspaper, The Observer, commissioned me to write a small piece on it, based on a related photography book, The Blindest Man by Emily Graham, published last year. In the course of research, I quickly stumbled on the conflict at the heart of this folly, between the author who wrote the puzzles, Régis Hauser, and the artist who designed the golden owl statue, Michel Becker; the present-day hunters were apparently factionalized in support of one or the other. Not only that, but there was also an outraged and indefatigably litigious former chouetteur, Yvon Crolet, who alleged that the hunt had been a fraud since day one.

It was total catnip. There was clearly scope for a longform story detailing the history of On the Trail of the Golden Owl, rooted in the personalities that had conceived it or been drawn into its chaotic orbit. But I still had a sense of fatigue when I thought about plunging in. I had written several stories in recent years that touched on people caught up inside obsessions and, in some cases, frauds: a museum in the south of France where 60 percent of the collection was fake, a purported scam involving the world’s oldest person, the controversy over a serial killer of cats in the south of England. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go over similar ground again — especially as that kind of shifting, uncertain terrain has a tendency to drive your humble writer slightly bananas as he tries to beat a narrative path through it.

But as J.G. Ballard once said: “Be faithful to your obsessions.” (And it seems particularly rude not to if your obsession is obsessiveness itself.) Even in my initial interview with Yvon Crolet for the Observer piece, I sensed this was familiar and fertile territory for me. He was the game’s ultimate player. So immersed was he in Hauser and Becker’s creation that when he failed to find the statue, he constructed a criminal case equally fastidious against them. I wondered if he wasn’t over-investing in that too. The Golden Owl hunt contained these questions of truth, verisimilitude, suspension of disbelief and credulity — close to all writers’ hearts — in its twinkling topaz eye. And it was the symbol of wisdom, too: chef’s kiss!

I was also slightly dreading attending the two chouetteur conventions scheduled for the game’s 30th anniversary year: one for the newly created AOC club that supported Becker in Rochefort, a naval town close to France’s west coast; the other for the veteran A2CO association in Bourges, the starting point for the hunt in the country’s epicentre, as revealed in the first riddle. Wouldn’t that mean being bombarded with the puzzles’ arcana — which I was incapable of making heads or tails of — by legions of implacable nerds? But actually I had a fantastic time at both, blown away not only by the welcome, but the genuinely open-minded spirit of adventure and curiosity on display from almost everybody there. A few AOC members cautioned me about the sect-like atmosphere at A2CO, with attendees worshipping at the altar of the original creator, Hauser. But I didn’t see it: just a well-worn camaraderie that superseded whatever frustration there was from three decades of fruitless owl hunting.

If only working on the rest had been so easy. I’ve never had so many people threaten to pull cooperation, or actually do so, on any other article I’ve worked on before. I felt I was constantly treading lightly with regard to people’s perception of the game, further proof of how this labyrinthine structure enveloped and forced allegiances out of everyone close to it. One chouetteur, offended by my characterization of Hauser at a point where I was struggling to understand his role in the clutter of contractual snafus and judicial proceedings in the game’s early phase, dubbed me “Phil Hoax” (bravo!). Most frustrating was Michel Becker’s withdrawal of his cooperation with the piece. After a long initial interview, apparently rattled by this inquiry into his recent stewardship of the game, he soon refused to talk any further to me. Which was a shame, as I wanted to better understand his journey as an artist, see where the hunt fit into that and learn whether he believed in this hodgepodge aesthetic of knightly quest, French history and Dan Brown-isms — or whether it was something that simply fit his purposes.

In the final piece, I found myself reaching — as many chouetteurs also do — for plenty of religious metaphors: Hauser as the prophet, Becker the caliph, the golden owl the True Cross, the chouetteurs the faithful, Crolet the apostate. But even this agnostic felt a heady rush of fervor when, a month into my investigation, an anonymous whistleblower began leading Crolet on with promises of information that would blow the history of the Golden Owl hunt wide open. But belief can sweep you to dangerous places, and deciding which sources were worthwhile and credible was a huge part of writing this story.

I also learned that treasure hunting could help there too, in terms of staying in touch with the bigger picture. On the mini hunts organized at Rochefort and Bourges, I finally started to glom onto the headspace required to be a searcher. I still wasn’t much good at the mental decryptions and lateral logic leaps needed for the puzzles on paper, but different skills were needed out in the field. In Rochefort, I started off with a supposedly easy riddle that specified, somewhere within the vicinity of the Hotel Mercure, to “lift the forbidden and complete your keyring.” Arriving on the scene, there were plenty of chouetteurs stuttering back-and-forth like malfunctioning robots, interfering with the “Do Not Walk on the Grass” signs and coming up empty-handed.

But I realized that it was easier to spot clues in the wild if you didn’t solely follow your agenda and kept things loose. In the words of the great Bunk, from TV series The Wire, on the subject of crime scenes: “You got soft eyes — you see the whole thing. You got hard eyes — you stare at the same tree and you’re missing the forest.” Finally, walking out of the zone, I spotted a wall with a “No Parking” sign that was just outside of visibility on the way in. I lifted it to reveal an aperture with a printed message inside: “You’re not the first.” I may not have won this round, but I was psyched at merely having solved the puzzle. Amid all the partisanship of the Golden Owl hunt I’ve tried to keep a beady eye on both Hauser and Becker’s sides of the story and put what is verifiable down for the record. But soft eyes tell me there is still more out there waiting to be unearthed. Detectives, treasure hunters and journalists — brothers in arms after all.

Phil Hoad is a reporter, features writer and cinema critic based in the south of France. He has written for The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, al-Jazeera, The Atavist, Hyphen, The Face and Dazed & Confused.

Jesse Sposato is Narratively’s Deputy Editor.